STUDIES ON THE LIFE CYCLE OF SPIROCHETES*

VIII.

SUMMARY AND

COMPARISON OF OBSERVATIONS ON VARIOUS ORGANISMS

EDWARD D. DELAMATER, M.D., Ph.D., MERLE HAANES, M.D.,

RICHTER H, WIGGALL, M.D., AND DONALD M. PILLSBURY, M.D.

THE JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY 1951; 16:

231-56

From the Department of Dermatology and Syphilology,

University of Pennsylvania

Medical School (Donald M. Pilisbury, M.D., Director).

This study was supported in part by a grant from the United States

Public Health Service RG 1316(C) and in part by a grant from the

Rockefeller Foundation.

This and preceding papers of this series were

From the also supported in part by U. S. Army Grant #W-49-007-MD-473.

Presented at the Eleventh Annual Meeting of the Society for

Investigative Dermatology,

June 25, 1950 at San Francisco California.

[Note: Plates I-X - description and pictures – that were originally

printed on pages 234-253, are all shown after the text.]

The purpose of the present paper is to draw together and

compare the observations made on the nonpathogenic Nichols strain of

Treponema pallidum both as it occurs in thioglycollate medium (1) and

as it occurs in the embryonated egg (2) under anareobic conditions; the

Kazan (3), Reiter (4), and Noguchi (5) strains of nonpathogenic

Treponema pallidum as they occur in thioglycollate medium; and the

pathogenic Treponema pallidum as it occurs in the experimental

syphiloma in rabbit testes (6, 7). Preliminary observations on Borrelia

anserinum and Borrelia novyi will also be cited (8, 9). The methods of

observation, presented elsewhere (10, 11) have consisted of the use of

phase contrast microscopy and a newly developed stain which has proven

particularly effective in the study of stained impression smears of

infected rabbit testes and in blood films of chickens infected with

Borrelia anserinum, and of rats infected with Borrelia novyi.

The current presentation consists of a synthesis and

correlation of the observations presented in these previous papers. A

brief history of the subject has been presented in conjunction with

paper No. V (1), and will not be recapitulated here, as a general

review of spirochetes and spirochetal diseases is in preparation (12).

OBSERVATIONS

By means of the phase contrast microscope the following

general story of development of spirochetes appears to be consistent in

those organisms studied. The conditions governing the occurrence of the

forms observed and reported are under study. In the current

presentation representative plates from several of these organisms will

be presented in attempting to present the total picture as it has been

observed up to the present time.

Transverse fission. In the organisms so far

studied transverse fission appears to be the most important single

method of vegetative reproduction in spirochetes, especially as they

occur under optimal conditions in their biologic hosts. This process

has been defined by Dobell (13), Zuelzer (14), and others, as the only

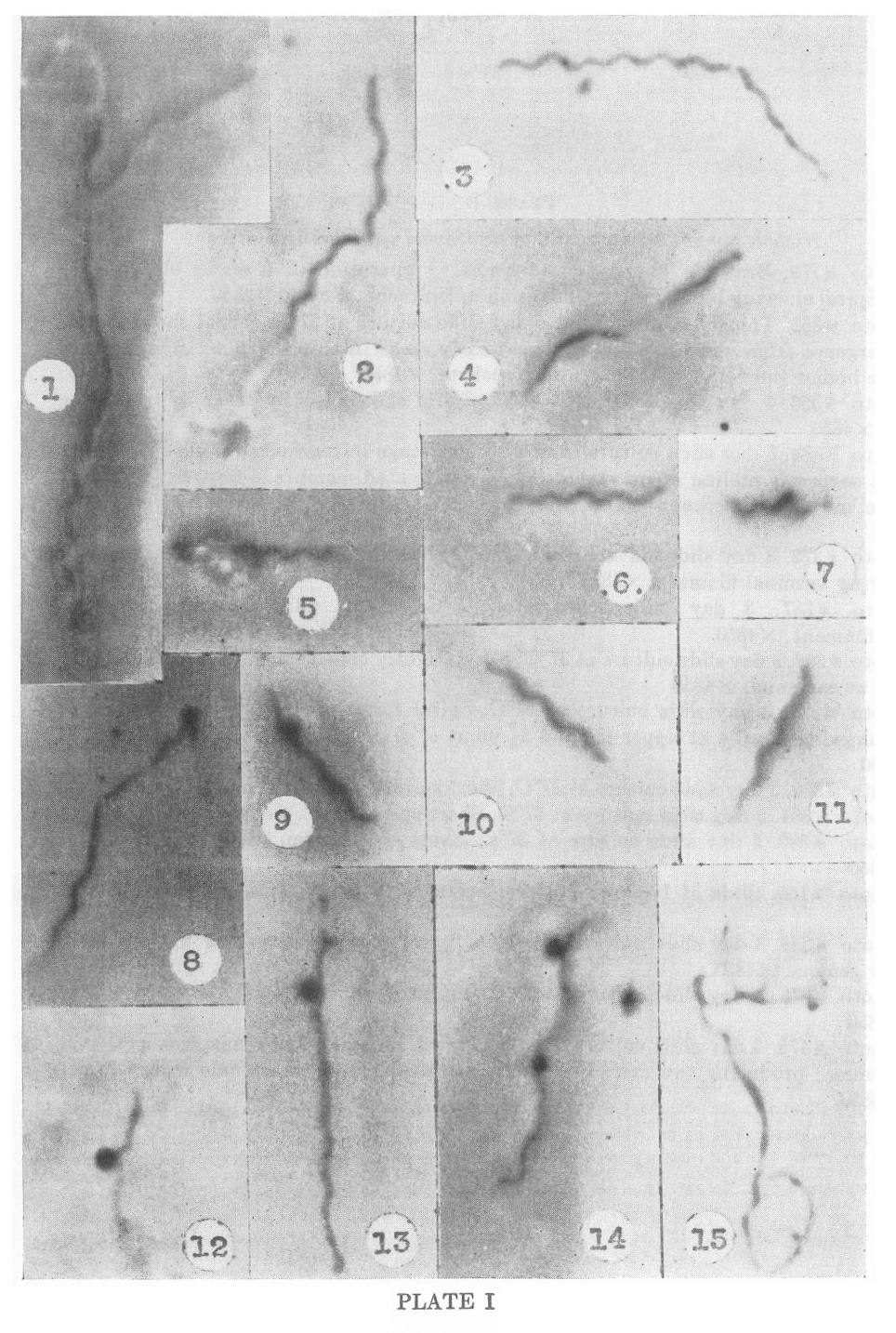

mechanism whereby spirochetes reproduce. In Plate I a series of stages

in the transverse division of the Nichols nonpathogenic Treponema

pallidum are presented. Similar observations have been made on the

Kazan, Reiter and Noguchi strains, as well as on the pathogenic

Treponema pallidum, Borrelia novyi, and Borrelia anserinum, as they

occur in the rabbit, rat and chick, respectively. The process of

transverse divisions begins with a rapid bending motion with the bend

always occurring at one point. A break presently appears in the

continuity of the spirochetal body, as shown in Figures 2, 3 and 8,

Plate I. After this break appears, the spirochete undergoes a brief

period of rest and subsequently a lashing motion again ensues. The two

spirochetal fragments, which are still attached by means of the

delicate filament, pull further apart but remain attached to one

another. The delicate membrane holding them together can be observed,

as seen in Figure 4. The organisms then begin a new twisting or spiral

motion in which they literally twist themselves apart and break the

tethering membrane. The long terminal filament so frequently observed

by ourselves (1—5) and many other authors (14), appears to be formed by

the remnant of the membranes which attach the two spirochetes together.

Such terminal filaments are observed in Figures 5 and 7, Plate I.

The point of rupture of the spirochetal body appears to be

associated with the point of attachment or origin of the flagella, as

seen in Figure 8. Recently, by means of improved lighting conditions it

has been possible to follow this process with great clarity, and almost

invariably the point of division is in juxtaposition to the point of

attachment of the flagella.

Transverse division as a means of reproduction is the

single most important method during the early most active phases of

young cultures, and during this period of development, from the first

to about the eighth day in our media, other methods of reproduction are

more difficult to demonstrate. After about the tenth day the

spirochetes begin to elongate and become more sessile, the flagella are

difficult to demonstrate and appear in many instances to be lacking, as

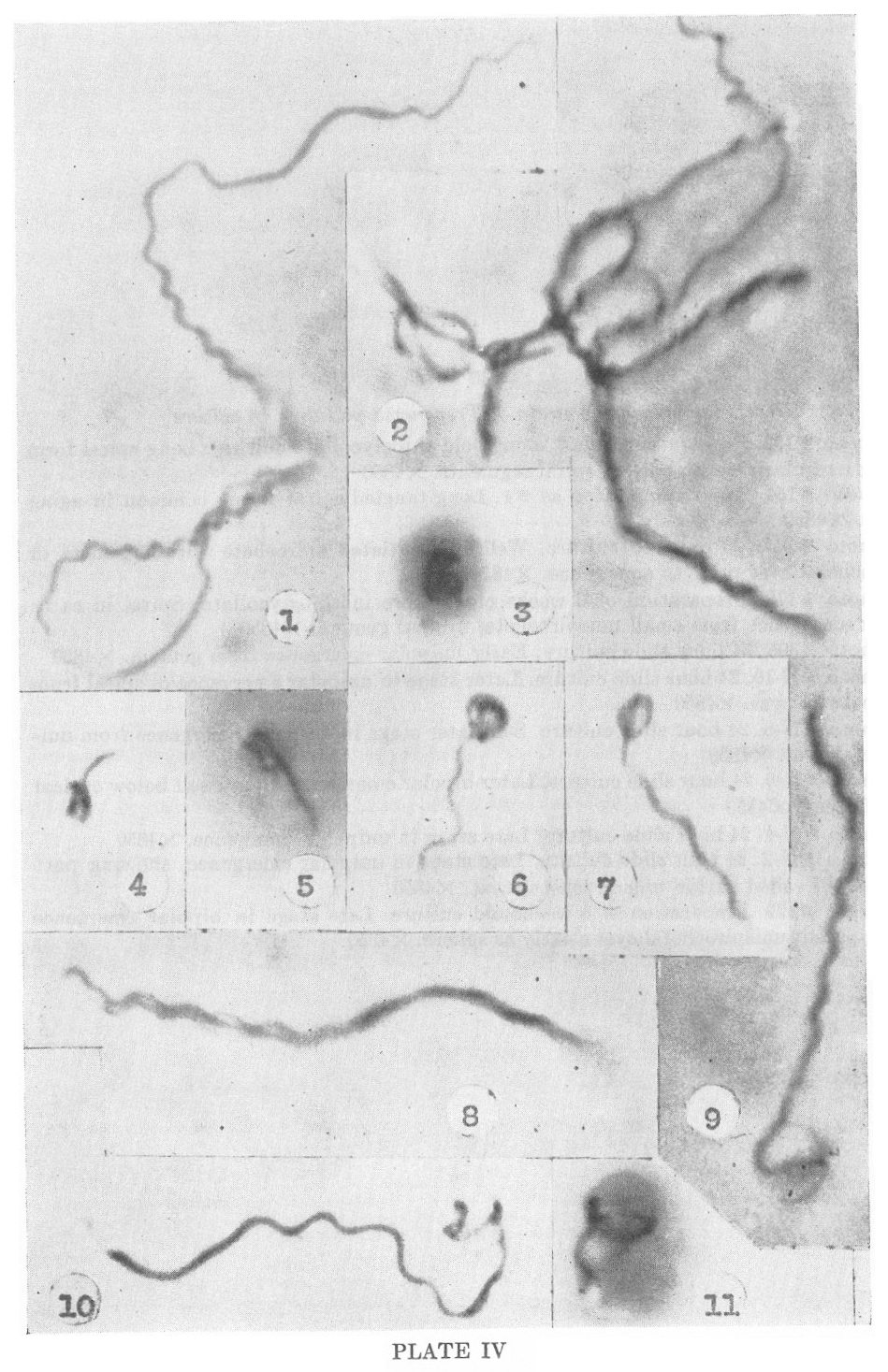

is seen in Figures 1 and 2, Plate IV. At about this same time the

elongating fragments of spirochetes previously produced by transverse

fission begin to form dense granules at any point along their bodies.

Production of gemmae as a means of vegetative reproduction.

The production of gemmae has been observed in all of the organisms

cited above except Borrelia novyi. This organism has not as yet been

adequately studied.

Gemmae, or buds, occur either as dense protuberances with

no inherent structure visible, as demonstrated in Figures 9, 12, 13 and

14, Plate I, or as seen in some of these early bodies, a delicate

limiting membrane can be demonstrated and a dense granule can be

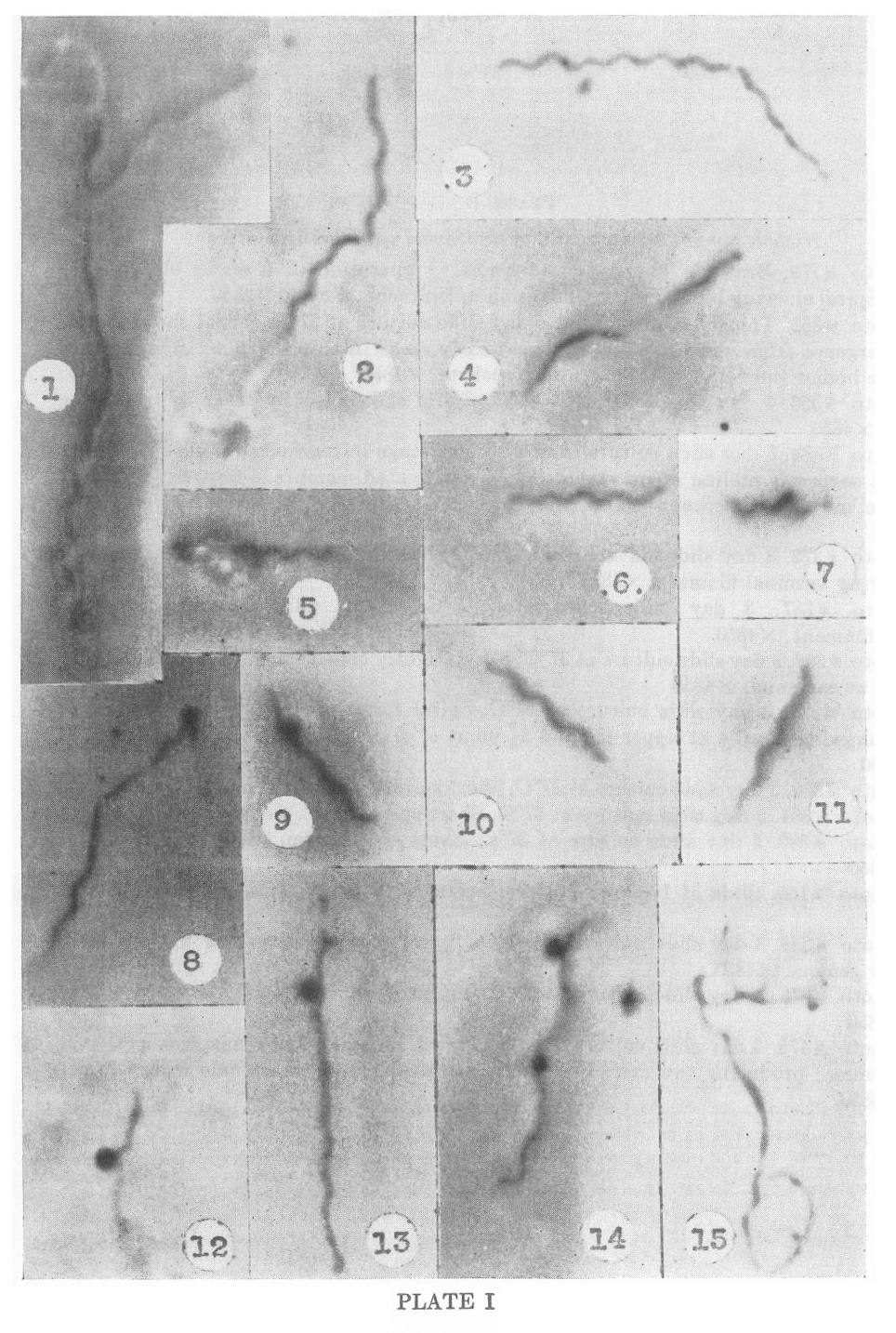

observed, usually attached at the base of these little cysts. Plate II

demonstrates the further production and development of these bodies

while still attached to the parent spirochete, and further demonstrates

that these bodies occur at any point along the spirochetal shaft. The

dense granules which can be visualized within them, as seen in Figure

11, Plate III, tend to elongate into curved rods, as seen in Figures 4,

10, 16 and 14, Plate II. It appears in the present stage of our

observations that the granule that becomes visible within these minute

cysts is the primordium of the daughter spirochete and that the

spirochete is produced by elongation and development of this granule.

Such a process of reproduction is essentially complex, and

it is hoped that future work will make it possible to elaborate on the

details of development.

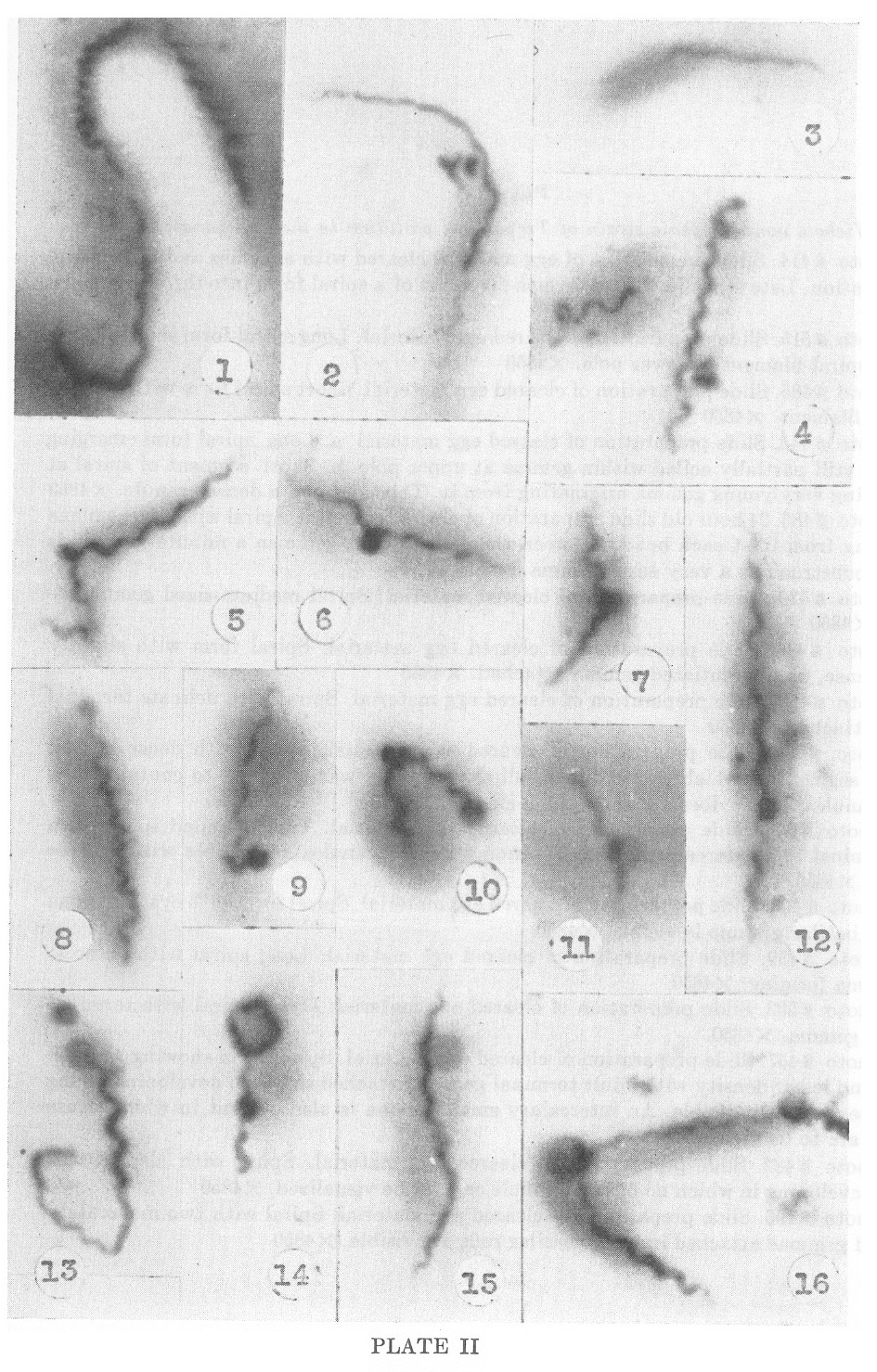

The gemmae may be dropped off by the parent spirochete at

any stage of their development, as demonstrated by Figures 1, 2 and 3,

Plate III. In Figure i the separation of a short segment of spirochete

with a granule attached is in process. In Figures 2 and 3 such bodies

have separated and in each figure delicate terminal filaments are to be

seen. This is best shown in Figure 3 in which the terminal filament

attached to the granule is observed to be spiral in the same manner as

the parent spirochete. Figures 4—24 show detached spirochetal gemmae in

various stages of development in some of which dense round granules are

visible and in others curved or twisted rods. Figures 26, 27 and 28

demonstrate fairly well differentiated young spirochetes still included

within their cysts, and in Figure 26 especially is the coiled character

of the organism visible. Figures 28, 29 and 30, Plate III, show very

early stages in the emergence of young spirochetes from such

unispirochetal cysts, while Figures 3—7, 9 and 10, Plate IV,

demonstrate later stages in the unipolar emergence of the organisms.

Figures 8 and 11, Plate IV, demonstrate the bipolar emergence of

individual organisms from such unispirochetal cysts and in such

instances the cyst may remain attached to the central portion of the

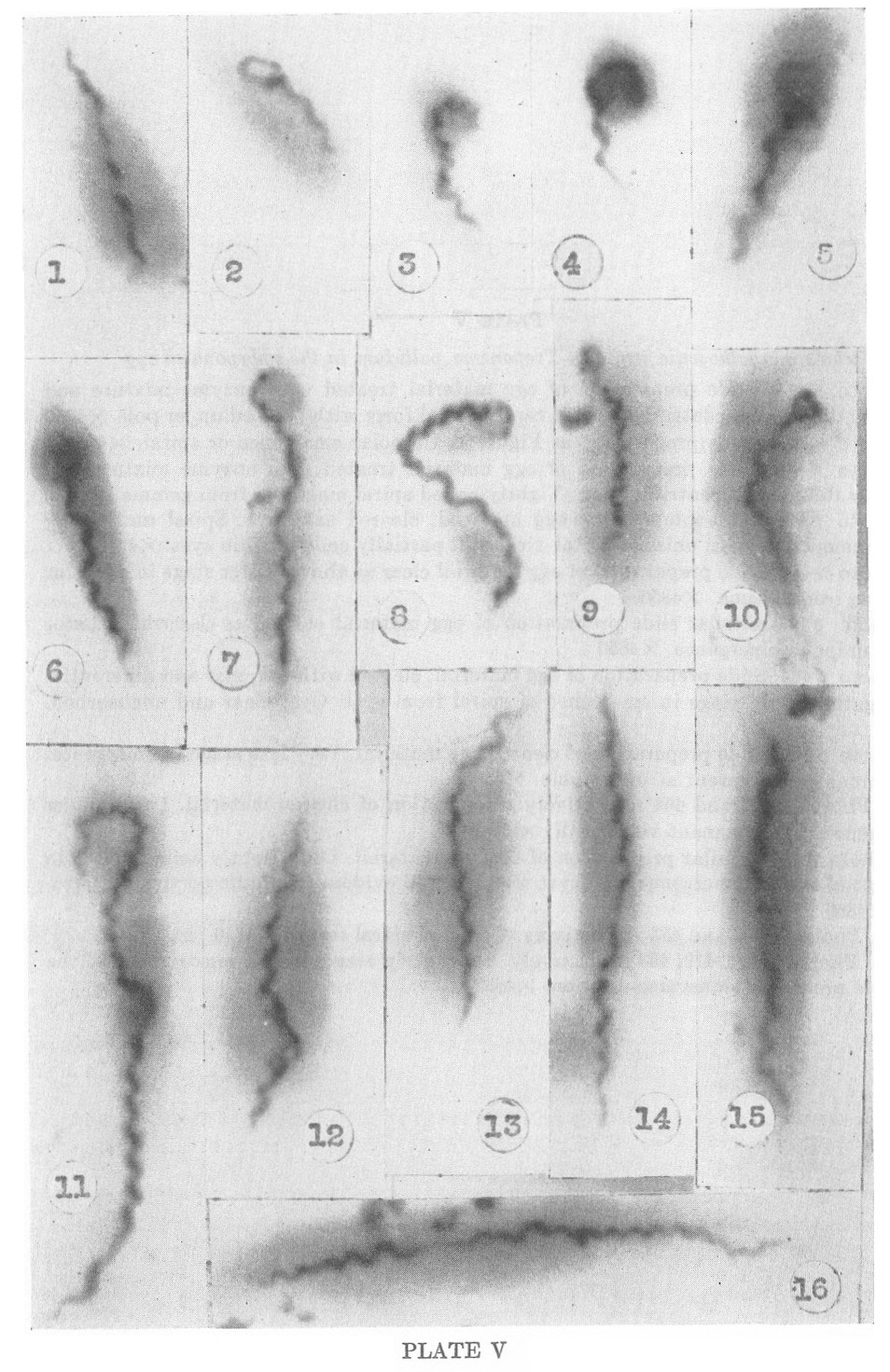

liberated spirochete, as shown in Figure 11, Plate V. Figures 3—10,

Plate V, show the persistence of the originating spirochetal cyst and

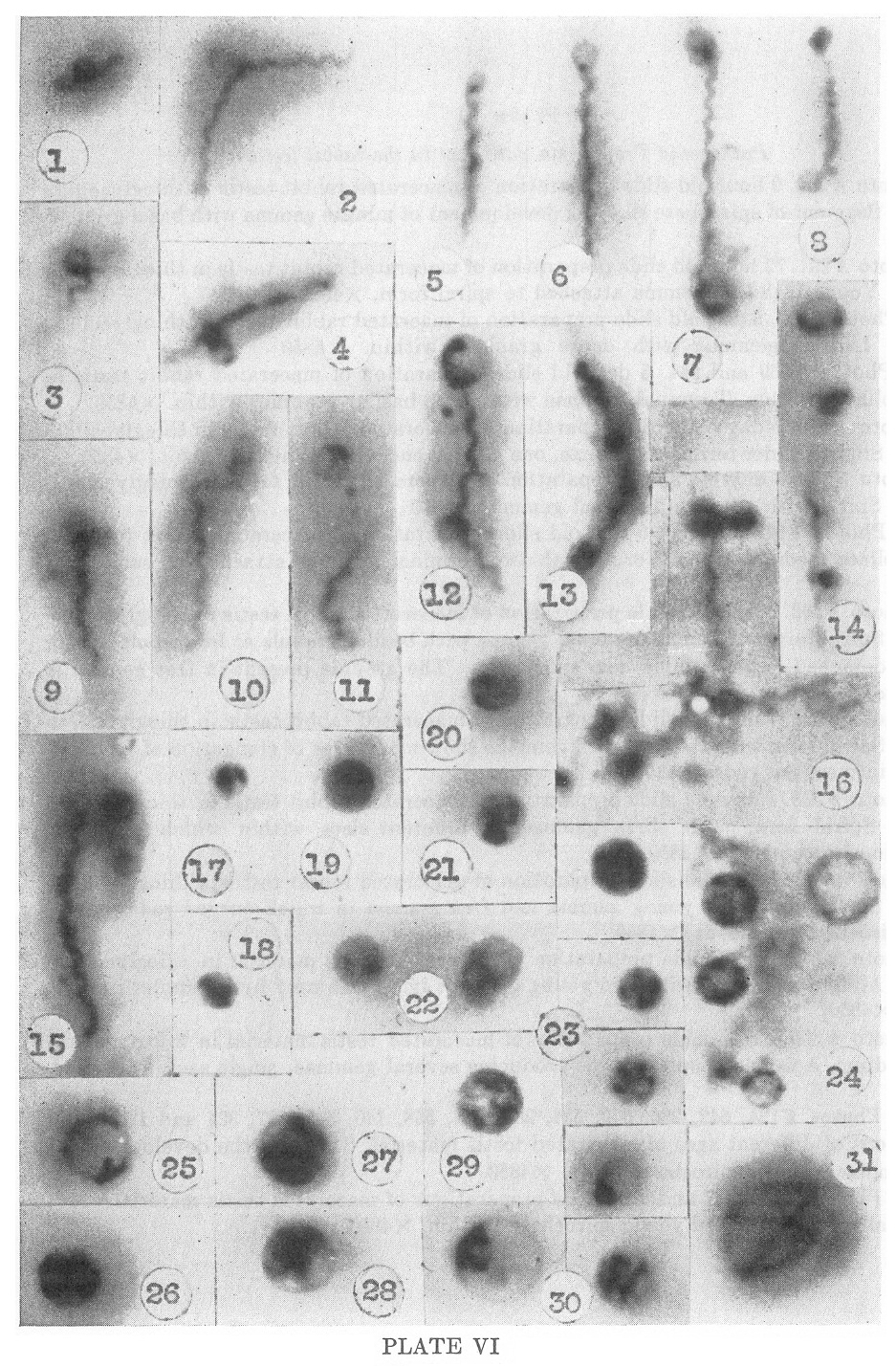

its resorption by the adult liberated organism. Plate VI recapitulates

the process as described for the pathogenic Treponema pallidum as

observed in the rabbit testis.

The production of multispirochetal cysts by the aggregation of organisms.

The following processes have been clearly observed in the Nichols,

Kazan, Reiter and Noguchi strains of nonpathogenic Treponema pallidum,

and in the pathogenic Treponema pallidum. Preliminary observations on

Borrelia novyi and Borrelia anserinum suggest that under certain

conditions similar forms may occur.

An additional method for the reproduction of spirochetes

appears to be by the formation of structures designated here as

multispirochetal cysts. These appear to be produced in two different

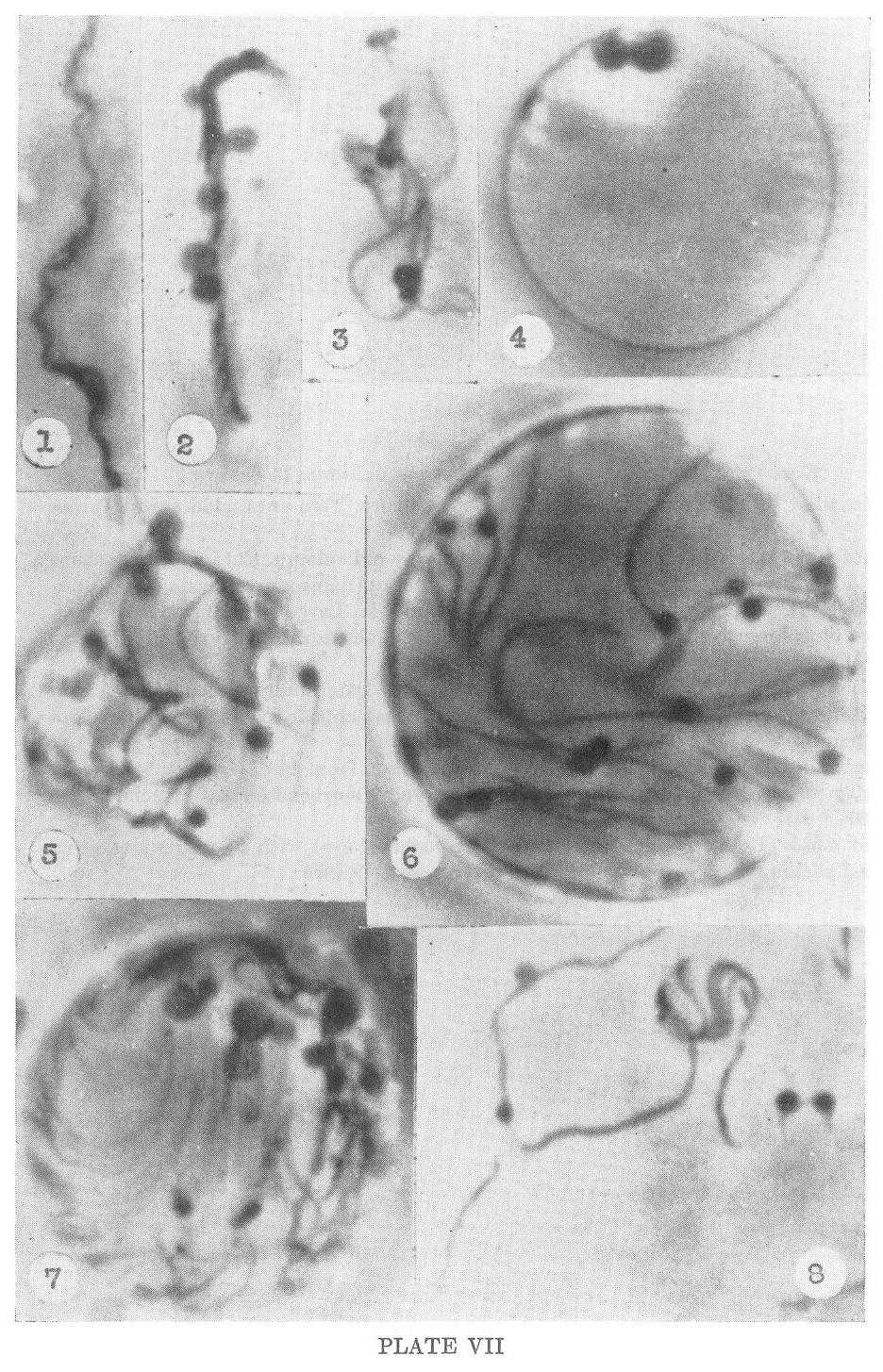

ways. Dense bodies form on clusters of aggregated or paired organisms.

These bodies are denser and larger than those which develop as gemmae

from single spirochetes. They enlarge to considerable size, as

indicated on Plate VII, and a limiting membrane is clearly shown in

Figures 4 and 6. The early stages in the development of these

multispirochetal cysts have yet to be worked out, as under present

conditions of study the internal structures have proven to be too small

for definitive observation. Recent developments in technic, however,

make it appear that it will be possible to study these processes in

more detail. At the present time it can be said that dense granules,

usually lying at one side or at the periphery of the cysts, appear to

reduplicate, forming dense aggregates. From these recognizable

spirochetal filaments develop, and to these granules, which are

currently interpreted as the primordia of individual spirochetes remain

attached, as seen in Figures 5, 6 and 7, Plate VII. In Figure 7 the

central body suggests the possibility that the granules or inclusions,

each of which forms a new spirochete, may reduplicate by a process of

budding. It will be readily seen that these multispirochetal cysts may

obtain tremendous size and may include very large numbers of organisms.

Figure 5, Plate VII, shows such a cyst in which the limiting membrane

has been ruptured. Emergence of adult forms from these large cysts will

be described presently.

The production of multispirochetal cysts by internal reorganization.

A second means of formation of these large multispirochetal cysts

appears to be by means of reorganization within a single spirochetal

body. Continued observation of these structures suggests that this is

probably the most important method of their formation. Stages in the

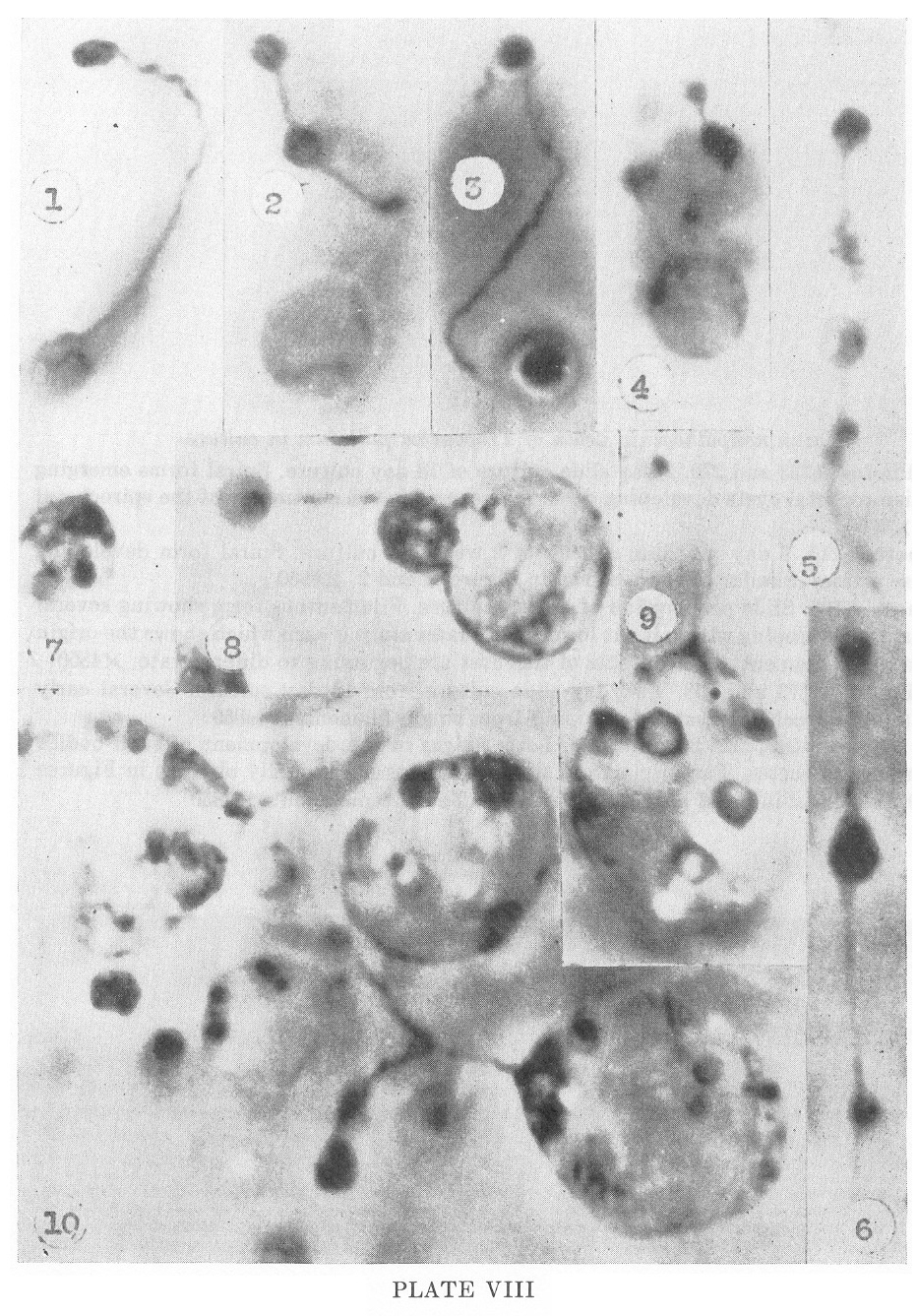

development and organization of these structures are seen in Plate

VIII. Figures 2, 5 and 6 show especially clearly the early development

of these bodies from within the continuity of a single spirochete, and

again the early stages of development remain obscure. It is apparent,

however, that the limiting membrane of the spirochete surrounds these

structures and that they are formed from within the continuity of a

single organism. In Figures 9 and 10 particularly, the continuity of

the limiting membrane of the parent spirochete can be observed to form

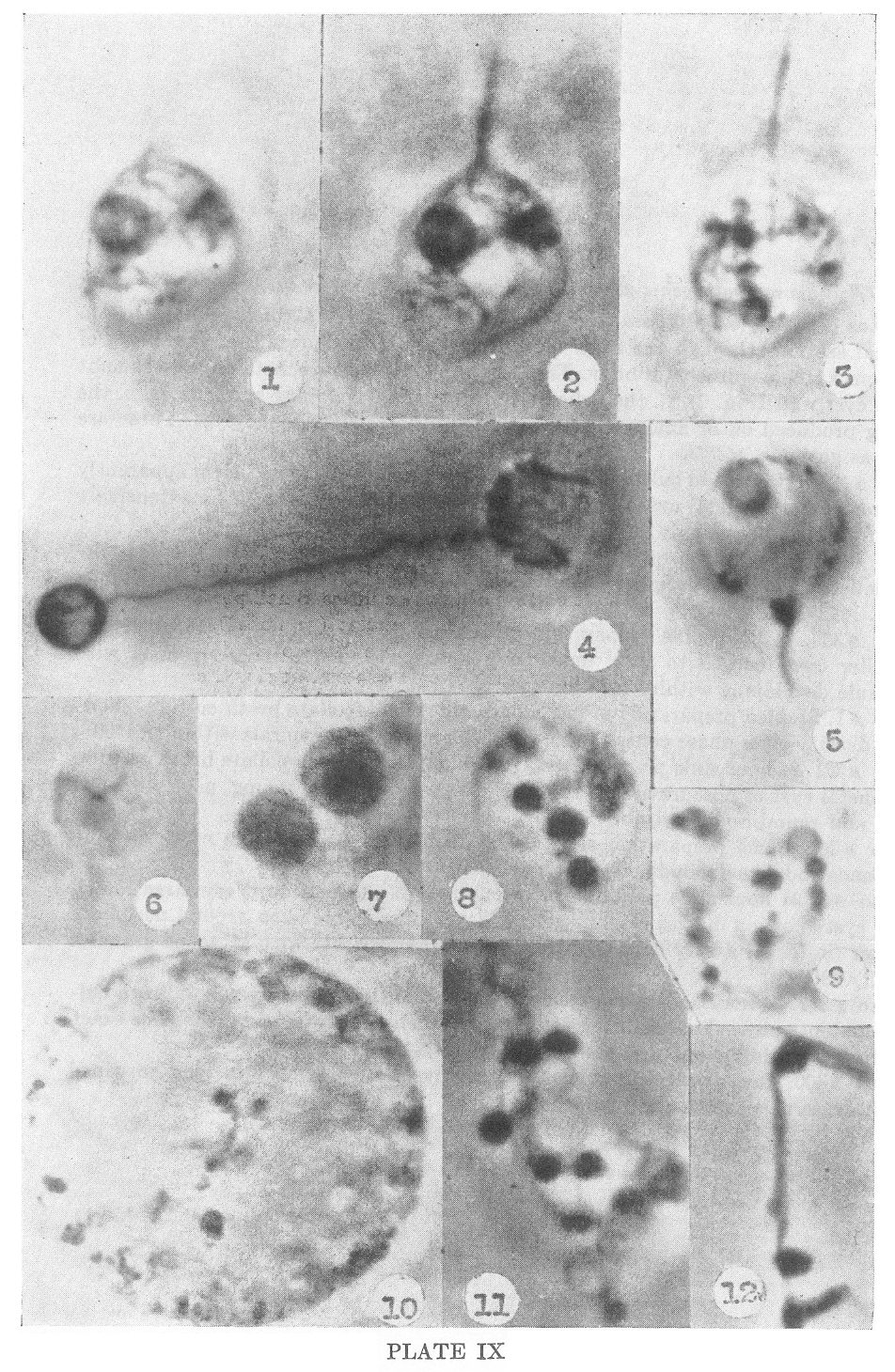

the cyst wall. This is shown in Plate IX, Figures 1, 2 and 3, which are

optical sections through the same multispirochetal cyst. As seen in

Figures 4, 7, 8, 9 and 10 of Plate VIII, these bodies enlarge

tremendously and numerous granules develop within them. Figures 9 and

10 are contents of crushed cysts showing minute granules and cystic

bodies in what appears to be the early developmental stages of the

daughter spirochete. In Figure 10 is shown a large cyst with numerous

inclusions in the center of which, in focus, is a delicate spirochetal

filament attached to a dense granule. Later stages of this

developmental process are again shown clearly in Figures 1, 2 and 3

where the developing spirochetal filaments can be readily observed, and

in Figure 3 the cystic granules are still evident. In Figure 12, Plate

9, is a section of a paired spirochete emerging from a cyst already

forming dense granules which appear to be comparable to the early

stages of development of multispirochetal cysts.

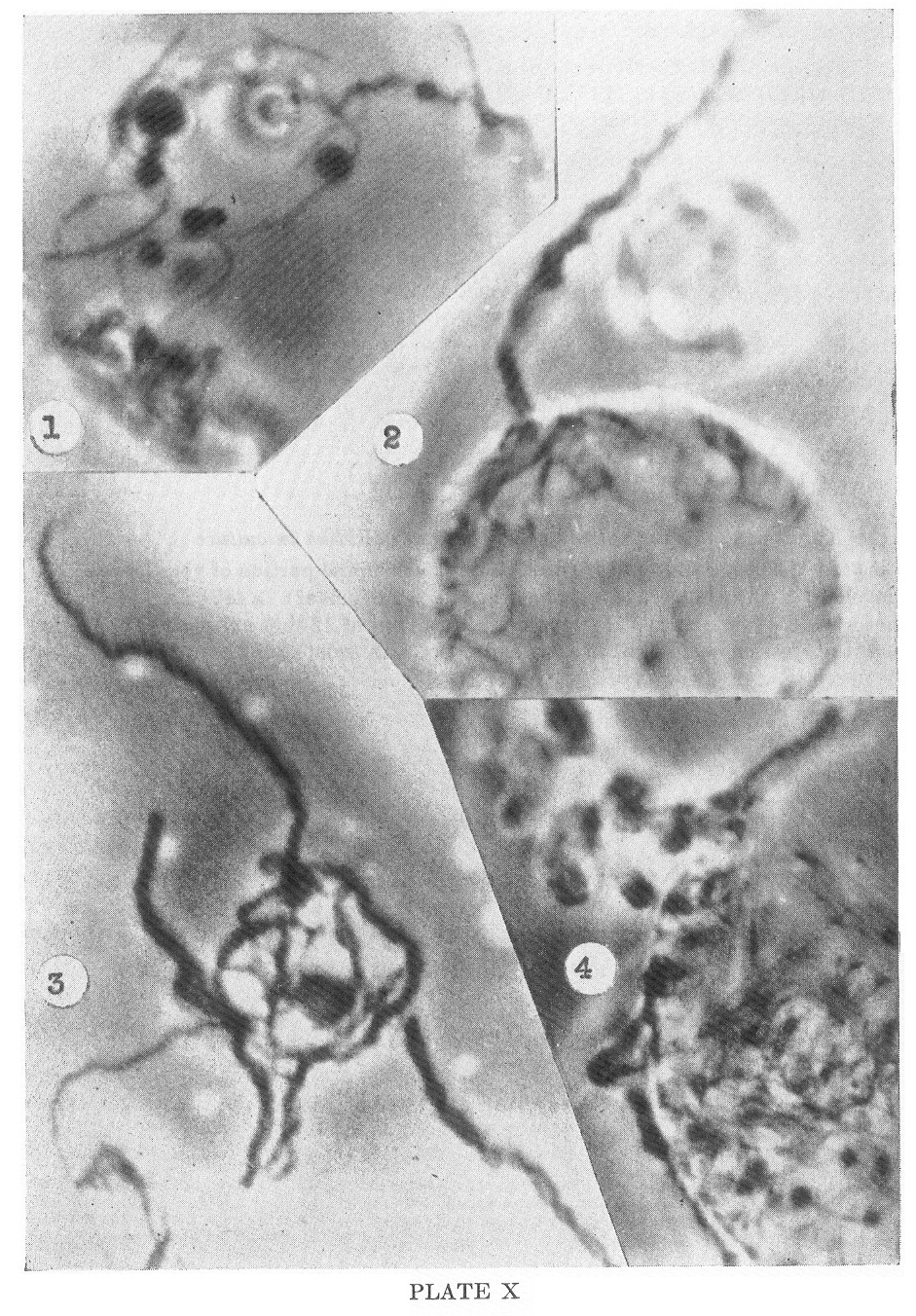

Release of the spirochetes from these multispirochetal

cysts is shown in Plate X, Figures 2, 3 and 4. When mature, the

spirochetes penetrate the cyst wall in massive cords or twisted ropes

and emerge in a manner demonstrated in these figures. Subsequently the

individual spirochetes separate one from another and undergo the

process of segmentation by transverse division and the formation of

unispirochetal gemmae.

The processes which have been described occur in the

cultured forms in old cultures, four to six weeks or more old. In

Treponema pallidum of the pathogenic spirochetes comparable structures

have been observed in material from lesions taken twenty-one or more

days after inoculation.

COMMENT

It is not yet known whether the processes described here are general

for all the spirochetes. Current studies, including observations on

Borrelia novyi and Borrelia anserinum, as well as other saprophytic isolates of Treponema

pallidum suggest that so far as these observations have been taken, we

are dealing with processes of reproduction which apply at least in some

degree in most spirochetes. Further studies will extend these

observations to include many other forms and very possibly modify

current working hypotheses as to the mechanisms of reproduction in

these organisms.

It is hoped that future studies will further elaborate the details of

the internal developmental process of both the unispirochetal and

multispirochetal cysts as well as the details of the association of two

or more organisms in the development of certain of these cysts.

It seems likely that the spirochetes should be considered

as a separate group of microorganisms distinct from the bacteria and

also distinct from the protozoa.

The current problems in the study of these organisms

necessitate the application of all available methods, including the

production of special staining methods, the further application of

electron microscopy, and the continued application, with modification,

of phase contrast microscopy. The most important single feature of this

latter technic appears to be the use of adequate illumination,

preferably of a monochromatic character.

Current studies must be considered at the present time to

be preliminary. Further development of the subject must depend upon a

continued accumulation of data and observations, and particularly upon

the development of pure cultural technics for the pathogenic forms so

that these may be studied under more highly controlled conditions.

REFERENCES

(1) DELAMATER, E. D., HAANES, M., AND WIGGALL, R., 1951: Studies on the

Life Cycle of Spirochetes. V. The Life Cycle of the Nichols

Nonpathogenic Treponema pallidum in Culture. Am. Jour. Syph., Gonorh.

& Ven. Dis. (in press)

(2) DELAMATER, E. D., HAANES, M., AND WIGGALL, R., 1951: Studies on the

Life Cycle of Spirochetes. VI. The Life Cycle of the Nichols

Nonpathogenic Treponema in duallsth pe Embryonated Hen’s Egg. Am. Jour.

Syphilis, Gonorh. & V. D. (in press)

(3) DELAMATER, E. D., HAANES, M., AND WIGGALL, R., 1951: Studies on the

Life Cycle of Spirochetes. VII. The Life Cycle of the Kazan

Nonpathogenic Treponema pallidum in Culture. Am. Jour. Syph., Gonorh.

& Ven. Dis. (in press)

(4) DELAMATER, E. D., HAANES, 1sf., AND WIGALL, R., Studies on the Life

Cycle of Spirochetes. Evidence for a Similar Life Cycle in the Reiter

Nonpathogenie Treponema pallidum in Culture.

(5) DELAMATER, E. D., HAANE5, M., AND WIGGALL, R., Studies on the Life

Cycle of Spirochetes. The Occurrence of Complex Growth Processes in the

Noguchi Nonpathogenic Treponema pallidum in Culture. (In preparation.)

(6) DELAMATER, E. D., WIGGALL, R., AND HAANES, M., 1950: Studies on the

Life Cycle of Spirochetes. III. The Life Cycle of the Nichols

Pathogenic Treponema pallidum in the Rabbit Testis as Seen by Phase

Contrast Microscopy. J. Exper. Med. 92: 239—246.

(7) DELAMATER, E. D., WIGGALL, R., AND HAANES, M., 1950: Studies on the

Life Cycle of Spirochetes. IV. The Life Cycle of the Nichols Pathogenic

Treponema pallidum in the Rabbit Testis as Visualized by means of

Stained Smears. J. Exper. Med. 92: 247—252.

(8) DELAMATER, E. D., AND HAANE5, M.: Studies on the Life Cycle of

Spirochetes. Observations on the Life Cycle of Borrelia anserinum. (In

preparation.)

(9) DELAMATER, E. D.. AND HAANES, M.: Studies on the Life Cycle of

Spirochetes. Observations on the Occurrence of a Life Cycle in Borrelia

novyi. (In preparation.)

(10) DELAMATER, E. D., HAANES, M., AND WIGGALL, R., 1950: Studies on

the Life Cycle of Spirochetes. I. The Use of Phase Contrast Microscopy.

Am. J. Syph., Gonor. & Ven. Dis. 34: 122—125.

(11) DELAMATER, E. D., HAANES, M., AND WIGGALL, R., 1950: Studies on

the Life Cycle of Spirochetes. II. The Development of a New Strain. Am.

J. Syph., Gonor. & Ven. Dis. 84: 515—518.

(12) DELAMATER, E. D., URBACH, F., AND HAANES, M. : Studies on the Life

Cycle of Spirochetes. Historical Review and Correlation with Current

Studies. (In preparation.)

(13) DOBELL, C. C., 1912: Researches on the Spirochetes and Related Organisms, Arch. f. Protistenk 26: 117—240.

(14) ZUELZER, M., 1925: Die Spirocheten. Handbuch der Pathogenen Protozoen 11: 1627— 1797.

DISCUSSION

DR. ARTHUR C. CURTIS: I think the work of Dr. DeLamater

and his coworkers is a major scientific contribution. It is interesting

to look at the cyst-like bodies of the spirochete he has shown and

wonder whether some might not be resting forms of the organism. Dr.

Wile has for many years believed a “spore-like” or resting form of

syphilis occurs. We have done experimental studies in mouse syphilis

and have been unable to find spirochetes after exhaustive darkfield

search throughout their brain tissue, yet after inoculation of this

material into rabbit testicles syphilis occurs. It may be possible that

these cyst-like bodies instead of spirochetes were present and when

they are put into a more favorable medium, they again develop into

spirochetes and produce the disease.

DR. STEPHEN ROTHMAN: I would like to ask the authors

whether the formation of cysts, development of spirochetes in the cysts

and their breaking through the wall has been directly observed, or

whether the cycle is reconstructed from single still pictures as

observed in the phase microscope.

DR. S. WILLIAM BECKER: I am sure that those who saw Doctor

DeLamater’s exhibit at the Academy in December were very much impressed

by it. I think it should be explained that under the phase microscope

you see first highly refractive bodies followed by red ones which can

be very well identified. Certainly these pictures are the best method

of visualizing the spirochete.

DR. DONALD M. PILLSBURY: We have had the same feeling as

Doctor Curtis; certainly in organisms fresh out of tissue they tend to

divide by transverse fission and form small gemmae and large cysts. It

is hard to say that it represents one spirochete. In spite of the hot

summer, there is a project on to take moving pictures and we may get a

little better idea of what actually occurs.

PLATE I

Nichols nonpathogenic strain of Treponema pallidum in culture

1. Photo #179. Brewer’s Thioglycollate media. Preparation of 6 weeks

old cultures at 37°C. Spiral showing bipolar emergence from

unispirochetal cyst. X4850

2. Photo #352. Thioglycollate media. 1 day slide culture at 37°C.

Spiral showing unipolar emergence from unispirochetal cyst and early

stage in transverse division. Several chromatic bodies (nuclei?)

visible within spirochete. X4850

3. Photo #356. 1 day slide culture at 37°C. Spiral showing early stage in transverse division. X4850

4. Photo #388. 3 day slide culture at 37°C. Later stage in transverse

division showing two short segments pulling apart with delicate,

attenuated membrane between them. At this stage movement becomes spiral

and spirochetes literally twist themselves apart. X4850

5. Photo #372. 3 day slide culture at 37°C. Spiral partly emerged from unispirochetal cyst showing terminal filament. X4850

6. Photo #387. 3 day slide culture at 37°C. Short spiral segment showing terminal filament. X4850

7. Photo #398. 3 day slide culture at 37°C. Short, tightly coiled spiral form with delicate filaments at each end. X4850

8. Photo #374. 3 day slide culture at 37°C. Spiral form in early stage

of transverse division showing flagella at upper tip and at point of

division. Gemma forming at upper tip. X4850

9. Photo #390. 3 day slide culture at 37°C. Short spiral forming a gemma or bud. X4850

10. Photo #384. 3 day slide culture at 37°C. Short spiral form. X4850.

11. Photo #390. 3 day slide culture at 37°C. Short spiral form. (Same photoplate as 49.) X4850

12. Photo #165. Slide of 1 month culture. Spiral with small dense gemma attached. X4850

13. Photo #383. 3 day slide culture at 37°C. Spiral showing formation of very early and older gemma. X4850

14. Photo #378. 3 day slide culture at 37°C. Spiral form developing two dense gemmae. X4850

15. Photo #475. 5 day slide culture at 37°C. Spiral emerging from

unispirochetal cyst (adult gemma) producing two early daughter gemmae.

Note dense granule within larger form. X4850

PLATE II

Nichols nonpathogenic strain of Treponema pallidum in the embryonated egg

1. Photo #414. Slide preparation of egg material cleared with enzymes

and differential centrifugation. Late stage in the transverse diversion

of a spiral form into three segments. X4850

2. Photo #515. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Long spiral

form showing long delicate spiral filament at lower pole. X4850

3. Photo #435. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Short spiral form with delicate terminal filament. X4850

4. Photo #445. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. a. Long

spiral form emerging from and still partially coiled within gemma at

upper pole. b. Short segment of spiral at left showing very young gemma

originating from it. This contains a dense granule. X4850

5. Photo #486. 24 hour old slide preparation of cleared material.

Spiral with two gemmae originating from it at each bend. Between these

two larger gemmae a minute granule is present, construed as a very

early gemma. X4850

6. Photo #473. Slide preparation of cleared material. Spiral medium-sized gemma attached. X4850.

7. Photo #446. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Spiral form

with slightly larger, dense, undifferentiated gemma attached. X4850

8. Photo #450. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Spiral with delicate terminal gemma attached. X4850

9. Photo #454. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Spiral with

dense curved terminal segment of which the terminal ball-shaped body

was observed to contain three dense granules. Photo does not show these

clearly. X4850.

10. Photo #438. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Tightly

coiled spiral form with terminal and intercalary gemmae forming dense

granules are visible within these gemmae. X4850

11. Photo #404. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Spiral form

with cystic gemma in which basilar granule is visible. X4850

12. Photo #459. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Long spiral with intercalary gemma forming. X4850

13. Photo #502. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Dense spiral with terminal stipitate gemma. X4850.

14. Photo #457. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Spiral form

showing areas of greater and Jesser density with adult terminal gemma

attached in which developing young spirochete is clearly visible. An

intercalary small gemma is also present iii which dense granules are to

be seen.

15. Photo #482. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Spiral with

clear cystic gemma developing in which no basilar granule can yet be

visualized. X4850

16. Photo #496. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Spiral with

two moderately advanced gemmae attached iii which basilar rods are

visible. X4850

PLATE III

Nichols nonpathogenic strain of Treponema pallidum in the embryonated egg

1. Photo #478. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Spiral with

long delicate terminal filament with gemma which is attached to a

spiral segment attached to it. X4850

2. Photo #405. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Gemma still attached to fragment of spiral. X2425

3. Photo #509. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Gemma with

densely coiled spiral form within, with delicate spiral similar to

terminal filament attached to cyst. X4850

4. Photo #417. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Tight spiral

form emerging from gemma. Two small, free gemmae near spiral. X4850

5. Photo #437. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Adult spiral and two mediumsized free gemmac. X4850

6-15. Photos #430, 426, 477, 431, 426, 430, and 422. Slide preparations

of cleared egg material. Stages in the development of freed gemmae.

X4850

16. Photo #404. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Two

medium-sized gemmae within which delicate, young spiral forms can be

seen. X4850

17-24. Photos #511, 488, 423, 426, 488, and 484. Slide preparation of

cleared egg material. Further stages in the development of the gemma.

Note single masses within each. X4850

25-27. Photos #406, 512, 469 respectively. Slide preparation of cleared

egg material. Late stages in the development of gemmae into

unispirochetal cyste. Coiled spirochetes can be made out within each.

X4850

28-30. Photos #516, 426, 511, 409 respectively. Slide preparation of

cleared egg material. Late developmental stages of unispirochetal cyste

from which spiral forms are beginning to emerge. X4850

31. Photo #413. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Two spiral

forms in different stages of emergence from unispirochetal cysts. X4850

32-34. Photos #477, 424, 464, 354 respectively. Small cystic forms

containing two or more masses within, interpreted as early stages in

the development of multispirochetal cyste. X4850

PLATE IV

Nichols nonpathogenic strain of Treponema pallidum in culture

1. Photo #152. Preparation from 1 month old thioglycollate culture.

Long spiral form showing irregularly and regularly spiral segments.

X4850

2. Photo #154. Same preparation as #1. Long tangled spiral forms common in aging cultures. X4850

3. Photo #357. 23 day old culture. Well-differentiated spirochete within gemma or unispirochetal cyst prior to emergence. X4850

4. Photo #179. Preparation of 6 weeks old culture in thioglycollate.

Spiral in early unipolar emergence from small unispirochetal cyst or

gemma. X4850

5. Photo #395. 24 hour slide culture. Early unipolar emergence from gemma. X4850

6. Photo #N-10. 24 hour slide culture. Later stage in unipolar emergence of spiral from unispirochetal cyst. X4850

7. Photo #N-8. 24 hour slide culture. Still later stage in unipolar emergence from unispirochetal cyst. X4850

8. Photo #N-6. 24 hour slide culture. Later bipolar emergence. Cyst itself below optical plane of focus. X4850

9. Photo #N-4. 24 hour slide culture. Late stage in unpolar emergence. X4850

10. Photo #N-2. 24 hour slide culture. Late stage in unipolar

emergence, showing part of spiral still coiled within unispirochetal

cyst. X4850

11. Photo #179. Preparation of 6 weeks old culture. Late stage in

bipolar emergence showing parent unispirochetal cyst clearly as sphere.

X4850

PLATE V

Nichols nonpathogenic strain of Treponema pallidum in the embryonated egg

1. Photo #474. Slide preparation of egg material treated with enzyme

mixture and cleared by differential centrifugation. Average spiral form

with pointed upper pole. X4850

2. Photo #478. Same preparation as Figure 1. Unipolar emergence or spiral. X4850’

3. Photo #448. Slide preparation of egg material treated with enzyme

mixture and cleared by differential centrifugation. Tightly coiled

spiral emerging from gemma. X4850

4. Photo #500. Slide preparation egg material, cleared as above. Spiral

undergoing unipolar emergence from unispirochetal cyst. Still partially

coiled within cyst. X4850

5. Photo #441. Slide preparation of egg material clear as above. Later stage in unipolar emergence from gemma. X4850

6. Photo #443. Similar slide preparation of egg material cleared as described. Later stage in unipolar emergence. X4850

7. Photo #463. Slide preparation of egg material, cleared with enzymes

and differential centrifugation. Late stage in emergence of spiral from

cyst. Cyst clear and unabsorbed. X4850

8. Photo #460. Slide preparation of cleared egg material. Very late

stage in emergence. Cyst remnant sill present at upper pole. X4850

9-10. Photos #457 and 464 respectively. Preparation of cleared

material. Later stages in emergence. Cyst remnant very small. X4850

11. Photo #498. Similar preparation of cleared material. Long tightly

coiled spiral in final stage of bipolar emergence with cyst remnant

still evident in middle portion of spirochete. X4850

12-13. Photos #473 and 483 respectively. Common spiral forms. X4850

14-16. Photos #454, 419, 453 respectively. Show early stages in the

construction of the spirochete preceding transverse division. X4850

PLATE VI

Pathogenic Treponema pallidum in the rabbit testis

1. Photo #296. 9 hour old slide preparation of macerated rabbit testis

in thioglycollate medium. Segment of spirochete showing development of

minute gemma with basal granule. X4850

2. Photo #291. 72 hour old slide preparation of macerated rabbit testis

in thioglycollate medium. Young bleb-like gemma attached to spiral

form. X4850

3, 4. Photo #522. 5 day old slide preparation of macrated rabbit testis

in thioglycollate medium. Lateral gemmae with dense granules within.

X4850

5, 6. Photos #539 and 544. 5 day old slide preparation of macerated

rabbit testis in thioglycollate medium. Terminal gemmae with dense

basilar granules within. X4850

7. Photo #572. 7-day old slide preparation of macerated rabbit testis

in thioglycollate medium. Slightly older terminal gemmae, one at each

end with granules present. X4850

8. Photo # 339. 3 day old slide preparation of macerated rabbit testis

in thioglycollate medium. Spiral with stipitate terminal gemma. X4850

9, 10. Photos # 348 and 330. 5 day old slide preparation of macerated

rabbit testis in thioglycollate medium. Spiral forms with two terminal

gemmae attached at same end. X4850

11. Photo #563. 5 day old slide preparation of macerated rabbit testis

in thioglycollate medium. Spiral form with small terminal gemma with

basilar granule at lower pole, and a recently detached larger gemma

near upper pole. The granule present in free gemma is seen to be

elongating. X4850

12. Photo #574. 7 day old slide preparation of macerated rabbit testis

in thioglycollate medium. Spiral form with two attached gemmae showing

degrees of elongation of included granules into curved rods. X4850

13. Photo #533. 4 day old slide preparation of macerated rabbit testis

in thioglycollate medium. Spiral form with three gemmae of different

sizes within which early differentiation is occurring. X4850.

14. Photo #581. 5 day old slide preparation of macerated rabbit testis

in thioglycollate medium. Spiral form with young gemma and free gemma

mi which curved rod forming young spirochete is evident. X4850

15. Photo #547. 5 day slide preparation of macerated testis material in

thioglycollate medium. Adult spiral form with two young gemmae lying

free near by. Granules present in each. X4850

16. Photo #305. Fresh slide preparation of macerated testis material in

thioglycollate broth medium. A tangle of spiral forms producing several

gemmae, single and in clusters. X4850

17-29. Photos #124, 542, 286, 549, 534, 288, 541, 558, 14), 565, 537,

324 and 123. Slide preparations of different ages of macerated testis

material. Stages in the development of freed gemmae into unispirochetal

cysts. X4850

30-31. Photos #569, 537 and 529. Slide preparations of macerated testis

material. Unispirochetal cysts with coiled young spirochetes within.

X4850

PLATE VII

Kazan nonpathogenc strain of Treponema pallidum in culture

1. Photo #201. Slide preparation of 11 day old culture. Two entangled spiral forms. X4850

2-3. Photos #200 and 191. Slide preparation of 11 day old culture.

Entangled organisms producing dense masses which appear to eventuate

into multispirochetal cysts. X4850

4. Photo #194. Slide preparation of 11 day old culture. Large

multispirochetal cyst. Early stage of differentiation. Double mass at

top continues multiplication and differentiation. Wall of cyst clearly

shown. X4850

5. Photo #204. Slide preparation of 11 day old culture. Later

multispirochetal cyst that has been ruptured showing developing

spirochetes and what appear to be gemmae developing from them. X4850

6-7. Photos #212 and 220. 3 day old slide culture made from 14 day old

culture. Very large multispirochetal cysts showing entangled developing

spirochetes and attached gemmae. X4850

8. Photo #526. (Reiter Strain) Smaller multispirochetal cyst with

filaments emerging. Dense spiral within cyst. No gemmae present within

cyst. X4850

PLATE VIII

Kazan nonpathogenic strain of Treponema pallidum in culture

1-2. Photos #233 and 270. 2 day slide culture of 18 day culture. Spiral

forms emerging from unispirochetal cysts developing dense masses within

the continuity of the spirochetal bodies. X4850

3. Photo #215. 3 day old slide culture of 2 week old culture. Spiral

form developing two dense masses. Similar to those shown in Figures i

and 2. X4850

4. Photo #196. Slide preparation of 12 day culture. Filamentous form

showing several dense masses developing within it. At lower pole a

later stage is seen which shows the origin from the single filament.

The contents of this cyst are beginning to differentiate. X4850

5-6. Photos #273 and 268. Two day slide culture from 18 day culture.

Several early masses (multispirochetal cysts) developing from single

filaments. X4850

7-10. Photos #247, 222, 206, and 266. Later stages in the development

of such bodies from single spirochetes. The origin from single

filaments is especially obvious in Figures 9 and 10. Details of

internal differentiation are difficult to make out. X4850

PLATE IX

Nichols nonpathogenic strain of Treponema pallidum in culture

1-3. Photos #56, 58, 59. Preparation of 6 weeks old culture in

thioglycollate broth. Three optical sections through the same

multispirochetal cyst showing: a. the Origin of the cysts from a single

spirochetal body. The membrane of the spirochete appears to split to

form the cyst wall (Fig. 2). b. the delicate fibrils of the developing

spirochetes. c. the bodies being produced on or among these young

spirochetes within the cyst. These are interpreted as gemmae. X4850

4. Photo #187. 6 weeks old culture in thioglycollate broth. Long spiral

form apparently emerging from unispirochetal cyst at right, within

which it can be seen to be extensively coiled, and forming a dense body

at opposite pole. X4850

5. Photo #160. Preparation of one month old culture in thioglycollate

broth. Large cyst wall; delicate spirals at periphery of cyst cut in

cross section, and mass developing within cyst. X4850

6. Photo #369. 24 hour slide preparation of one month old culture in

thioglycollate broth. Smaller cyst focused to show developing

spirochete and attached gemma with basilar granule developing within.

X4850

7. Photo #1. Stained preparation of one month old thioglycollate broth

culture, showing greater density than phase contrast preparations and

delicate spirals within. X4500

8. Photo #361. 24 hour slide preparation of one month old

thioglycollate broth culture. Multispirochetal cyst of obscure origin,

showing cyst wall and very young, poorly-defined spirochetes and round

bodies within. X4850

9. Photo #363. Same preparation as 8. Cyst contents pressed from cyst, showing delicate strands and dense round bodies. X4850

10. Photo #3. 24 hour slide preparation of one month old culture. Very

large multispirochetal cyst showing masses of very young, developing

spirochetes around periphery and in center (in focus) a very delicate

irregular young spirochete with attached granules (gemmae?). X4850

11. Photo #371. 24 hour slide preparation of a one month old

thioglycollate broth culture. Cyst contents pressed out showing dense

masses, delicate fibrils and blebs. The exact nature and organization

is obscure. X4850

12. Photo #400. One month old culture in thioglycollate broth. Two long entwined spirals with dense masses attached. X4850

PLATE X

Kazan nonpathogenic strain of Treponema pallidum in culture

1. Photo #236. 3 day old slide culture of 12 day culture. Small portion

of very large cyst showing developing spirochetes and attached granules

(gemmae?). X4850

2-4. Photos #217, 209, and 225. 3 day old slide culture of 12 day

culture. Very large multispirochetal cysts showing emergence of

spirochetes in twisted cords. X4850